Drug testing fails to decrease substance use

Creative commons photo courtesy of the Drug Abuse Resistance Education

DARE is the most widely used prevention program in American education. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/

March 9, 2020

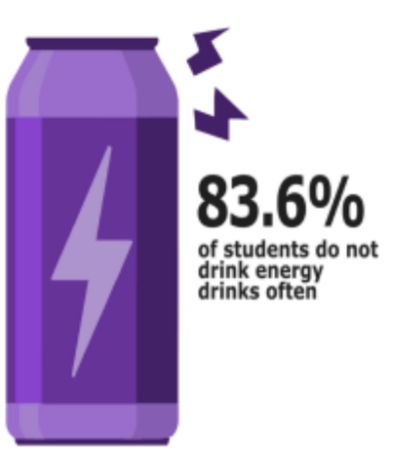

The odds are extremely high that the average high schooler has had a run-in with the Drug Abuse Resistance Education (DARE) program. It’s the most widely used prevention program in American education, but its quality isn’t on par with its quantity, or so scientific research from PBS has proven. Introducing the vast majority of middle schoolers to drunk goggles and the study of Schedule 1 drugs hasn’t helped us win our tragic drug war, but it isn’t our only option.

In comes school drug testing to potentially pick up where DARE leaves students off. Under this policy, schools would embrace a more paternalistic attitude, randomly putting kids through “non-suspicion based screening for drug use.” Instead of turning a blind eye to adolescents and hoping they’ll use their newfound knowledge of drugs and alcohol for good, these tests aim to seek and destroy the drug use wherever it crops up. Skeptics might be concerned about student privacy, but look at the bigger picture. If you have nothing to hide, you have nothing to fear, as we often hear. The public shouldn’t hide from such a big policy win.

Yet even when putting aside all moral quandaries, this policy does not pass the same test that failed DARE: the ultimate test of its own results. The ACLU compiled studies ranging from more openly biased sources like the libertarian Cato Institute to non-partisan sources like public universities and the American Academy of Pediatrics, and despite the differences in ideological biases, the studies agree that drug tests are just another case of unintended consequences. As Cato scholar Robert Taylor summarizes, “Not only does [drug testing] invade the privacy of a group of students who are relatively unlikely to use drugs, but it also discourages athletic participation and may actually lead to an increase in overall drug use.” Of course, the entire field of research testing isn’t unanimous in its criticism. The Center On Addiction states that at worst, the body of evidence is “mixed and inconclusive.” This doesn’t sound like much of a clear-cut win.

It’s in everyone’s best interest to ask “and then what?” whenever any solution is presented for a problem, but asking this question hasn’t revealed a good answer to the epidemic of dangerous drugs. We might not have found the long-term fix that we’re looking for, but the short term is still brighter than the past. The US has just seen the first drop in overdose deaths in three decades. As we work to fix DARE and drug testing, let’s pray that this current trend is here to stay.