Controlling an industry does not eliminate competition

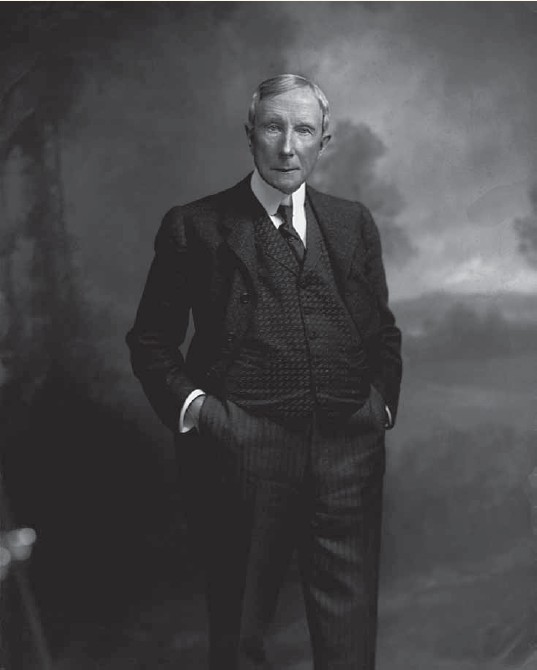

Creative commons photo courtesy of Oscar White

John D. Rockefeller, owner of Standard Oil – the only big oil company in the 1890s.

May 8, 2020

Right behind journalism teacher Wayne Woolley’s desk in 107 stares the famous muckraker Ida Tarbell. She’s attacking Rockefeller’s Standard Oil – the only big oil company in the 1890s – for squeezing extra high profits out of the public, all because there was no competition to save the day. Tarbell and our history classes have taught us the timeless argument that these monopolies need to be broken up, but it’s a little more complicated; while competitors may have disappeared where the government sees a monopoly, competition can often stay strong. To demonstrate a few reasons why let’s take a look at a place that’s crawling with monopoly: Communications High School.

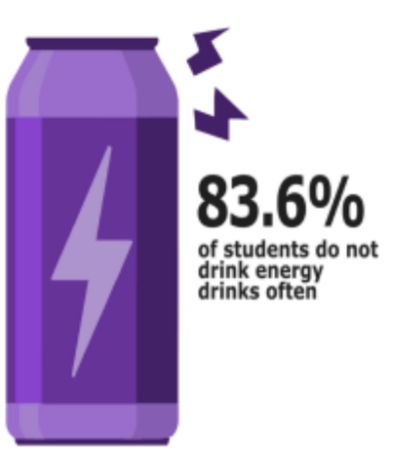

CHS students often purchase pretzels from an after-school monopoly: The Junior Exit Sale. The Juniors are the textbook definition of a monopoly, being the only seller in a given market (the market for CHS after-school pretzels), and yet they obviously aren’t able to get away with gouging their prices to whatever they want. While they may enjoy the status of being the school’s only source of hot pretzels after class, they still face ruthless competition from the students’ next best choices outside of their given market: the vending machine in the corner, the restaurants on route 35 or the choice of buying no food at all.

The federal government would probably say that fitness teacher and Class of 2021 adviser Ginny Clevenger has a monopoly, as it’s notorious for narrowly defining the “industry” that a supposed monopolist has control over. In the case of Brown Shoe Co. v. United States in 1962, the Supreme Court defined the market for shoes as only including “domestic production of non-rubber shoes.” If you look down at your shoes and see that you’re wearing sneakers, or if you see a tag that says “made in China,” then under this ruling you would not be looking at a shoe. If we’re going to follow the government’s historical footsteps and use this loose definition of an industry, then we can safely call Clevenger the J.D. Rockefeller of after-school snacks.

The alleged shoe monopolist that the Supreme Court went after still faced real competition from other shoemakers, but Stanford economist Thomas Sowell explains that a lack of competitors in an entire industry still doesn’t mean that competition itself has also weakened. Talk about a company controlling the market “…ignores the role of substitutes that may be officially classified as products of other industries, but which can nevertheless be used as substitutes by many buyers, if the price of a monopolized product rises…”

Monopolists must recognize that if they jack up their prices, then customers will seek out or create their own substitutes as time goes on. This is why the Aluminum Company of America, despite being the only producer of aluminum in America for decades, kept cutting its prices instead of gouging them up. They feared that their customers would switch to steel, tin or plastic. Even two things that seem wildly different can be used as substitutes for one another and foil a monopolist’s price-fixing plans, like when petroleum prices shot up in 2004 and producers started using corn for oil instead. The lesson in all of this is that it just isn’t enough for a company to have control over its own industry to save itself from the competition, which crops up in unexpected forms.

When headlines claim that monopolies are afoot and that they have killed competition, keep an eye on the specifics. The fact is, as Nobel Laureate George Stigler said, “Competition is a tough weed, not a delicate flower.”