For students and teachers alike, school can sometimes feel like a circus – especially when there’s donkeys and elephants involved.

The U.S. education system has filled its fair share of headlines in recent years. Whether it is book censorship or controversy over transgender students’ rights, politics have taken a seat in classrooms across the country. This comes during a time of division that has left many educators unsure of how to handle political discussion.

Since January 2021, 35 states have introduced a total of 137 bills limiting what schools can teach with regard to race, American history, politics, sexual orientation and gender identity, as NPR reports. Though this type of legislation has never survived the New Jersey Senate, schools across the state are feeling the fallout. At Communications High School (CHS), history teacher Sharyn O’Keefe spoke on the feelings of educators.

“Lately, there’s more fear in teachers’ minds from parental backlash about having [politics] spoken about, which I think is a scary thing,” she said.

For history teachers like O’Keefe, these topics can feel like a natural extension of their subject field and a necessary facet of a valuable education, a sentiment echoed by CHS Principal Emily Bonilla.

“What do you want students to be?” she asked. “You want them to be critical thinkers, you want them to be problem solvers, you want them to be involved in politics and be active citizens. So avoiding politics is hard.”

Approaching controversial topics is a challenge that most teachers across the country are choosing to avoid. According to a nationally representative survey by Rand Corp., 65% of K-12 teachers restrict instruction on “political and social issues”. This is nearly double the percentage of teachers that are actually affected by state laws that limit this type of instruction. The same report determined the reason for this: teachers worry that school or district leaders wouldn’t support them if parents expressed concerns. When asked about their approaches to politically charged topics, CHS teachers varied in their responses.

“Sometimes it does come up, sometimes it doesn’t. I don’t force it,” said O’Keefe.

CHS history teacher William Clark is more forward with his approach.

“We do a lot now,” said Clark. “I’m doing a pilot program with history, youth and public policy. For my U.S. I class, we do debates that cover a lot of different political topics, hot-button topics throughout the entire year.”

Though there is a lot to consider when facilitating this type of conversation, Clark believes the benefit is well worth it for students.

“I think it’s good to have because you learn from each other. It can’t be one homogenous view, we have so many different opinions and not everyone is so rigid in one way,” he said. “To me, political activism starts at an early age.”

Sophomore Avery Garr of Aberdeen is a student in Clark’s U.S. History I class and a firm supporter of a more politically focused curriculum. After taking part in class discussions, she approached Clark, who is now helping her form a civics club at CHS. She points out the need to better inform the future generations of voters.

“I don’t think people my age know how to speak about [politics] without using their parents’ opinions,” she said. “The goal of [the club] is to teach kids our age how to be future voters, how to prepare themselves for that and also properly inform them about what’s going on in the world.”

This sentiment is echoed by junior Sean Sharkey of Fair Haven.

“If we don’t talk about current politics, then we’re setting up kids to be unprepared for a democratic society,” said Sharkey.

However, not all students at CHS want to have these conversations in school. Junior Max Estrada of Tinton Falls believes there is a time and place to express political beliefs.

“I think you should keep personal politics out of school since everyone has different opinions and you should form them on your own, not in a group environment,” he said.

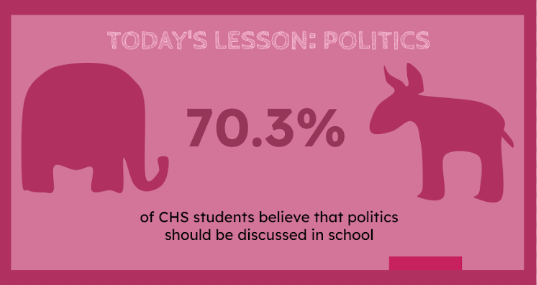

Though not alone in his viewpoint, Estrada represents an unpopular perspective at CHS. A recent school-wide survey determined that more than 70% of students believe politics should be discussed in school. A few students, even, believe that politics and present social issues are not discussed nearly enough; Sean Sharkey is one of them.

“No teacher has made any mention or reference to the election,” he said. “Especially in an election year, we should make an active effort for students to be taught what the current global issues are, why people should vote, why people have issues with voting and the differences between the two parties.”