Teenagers go for the bronze, but risk the red

Students comment on the risks and controversies surrounding tanned skin

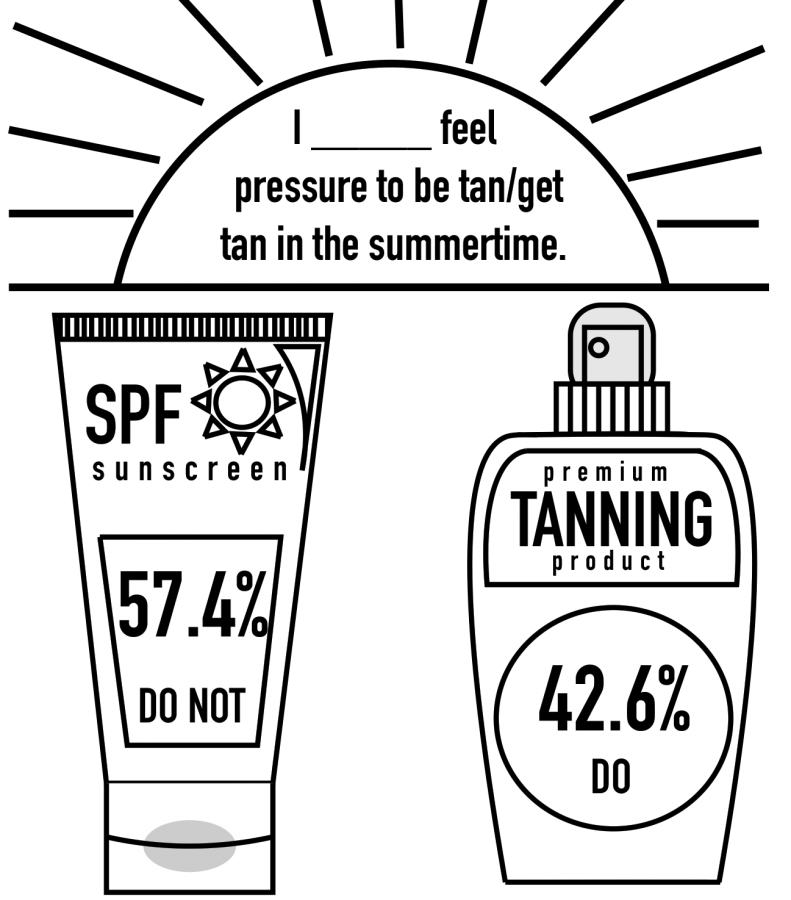

Survey of 47 students from August 18th to September 4th.

September 13, 2019

When summer hits, many teens and young adults head to the beach in pursuit of the perfect tan. However, the risks they’re grappling with may be more than skin-deep.

“I guess in some way it was in hopes of achieving a tan, but I ended up getting a horrible sunburn, and… I missed two days of school,” said junior Bella Carmona-Ramirez of Long Branch on the aftermath of a sunblock-less beach outing. “I was red for weeks.”

According to Fashionista, tans first became sought-after in the 1920s due to the influence of Gabrielle “Coco” Chanel. When Chanel was photographed with a dark complexion in the French Riviera, she changed Western ideals of beauty from that point forward. A new industry was born, and baby oil became a beach bag necessity.

However, in addition to the lingering redness and extreme peeling that Carmona-Ramirez experienced, consequences of overexposure to the sun include skin cancer, sun poisoning and wrinkles, according to Mayo Clinic. Senior Jillian Tracy of Belmar, while admitting she has a rocky relationship with her “notoriously pale” skin, says a natural tan is simply not feasible or safe for her.

“Skipping sunblock is not an option for me,” Tracy said. “I have gotten sun poisoning in the past and I have no doubt it will happen again if I’m not careful.”

For others with sun-exposure issues similar to Tracy’s, spray tans, done both at home and at salons, have become a popular way to maintain tan skin without the dangers of UV rays. According to American Spa Magazine, the spray tanning industry in the U.S. grew in value from $775.3 to above one billion from 2014 to 2017.

“Personally, I feel more confident and healthy with a tan,” said senior Riley Radamacher of Wall. Radamacher spent money to get a spray tan for her junior prom, and said it was the right choice for her due to the boost it gives her self-esteem.

“It hides any blemish that may be easily seen with pale skin,” Radamacher said.

The accessibility of spray tans, however, leaves many people wondering how much is too much. Senior Jack McHugh of Manasquan said for as trendy as tan skin is, natural beauty is what holds the most weight for him in terms of attraction.

“I think being more tan is attractive but… I personally do not like it when people get spray tans,” McHugh said. “It’s not real.”

Additionally, many artificial tan companies and social media influencers have come under fire for toeing the line between “sun-kissed” and “racially ambiguous.” As reported by Teen Vogue, social media users criticized spray tan brand Emmaatan and its customers for “appropriating people with darker skin without actually appreciating people of color.”

Emmaatan is not alone, as members of minority groups have also accused other companies and stars of profiting off a darker complexion while bypassing the racial discrimination that people of color face due to their skin tone. According to Teen Vogue, “This form of cultural appropriation is extremely offensive because it suggests that a race can be reduced down to a ‘costume’… the issue is much bigger than the act of darkening your skin; blackface dehumanizes and mocks an entire race.”

Junior Mahita Dasu of Marlboro, a teen with “an Indian background,” said that she doesn’t take tanning too seriously, but only to a point.

“Most of the time tanning turns out ugly so I find it amusing,” Dasu said. “I haven’t really seen dark skin on pale people much because the people I’m around tend to have some sensibility. But I guess if you’re trying to achieve a look… and appear to be of a totally different race, then you’ve crossed a line.”