Automation: a blessing in disguise for the unemployed

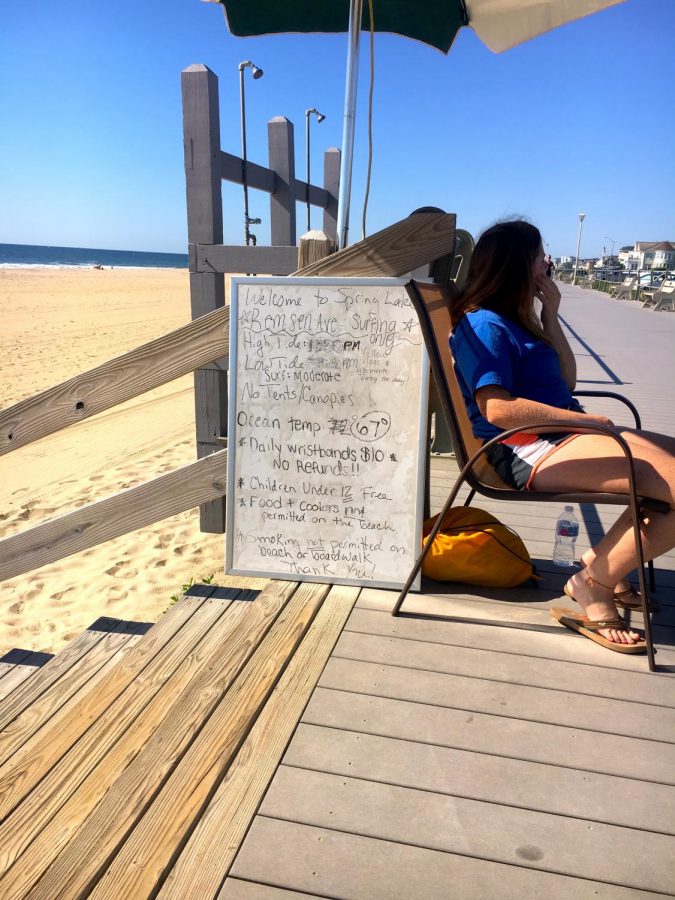

Blot courtesy of Riley Forrester

In the summertime, badge-checking is a popular job amongst teenagers. But this job may soon become obsolete due to increased technology.

June 20, 2019

It’s 2040. Kids around the world are dead broke, and at no fault of their own. Work just simply doesn’t exist. The “summer job” has become an obsolete novelty, ground under the boot of economic progress because a piece of machinery can do their jobs slightly more efficiently than they could ever do as human beings. And that’s the culprit of it all: cheaper, perfectable technology.

This future seems startling, distant and probably even overblown to most casual observers, but many researchers have reached their own conclusions that seem to support the doomsday hypothesis.

The Obama administration reported that more than 80 percent of jobs paying less than $20 per hour could be eliminated by 2030. It seems like every single worker in the United States is on the road to job destruction at the hands of new machines. This is scary, especially to young, inexperienced workers, but these fears lose their luster when pit against the bigger picture.

Automation horror stories are built on worldviews that define humans as producers, instead of as both producers and consumers. After all, jobs don’t exist because society said that it wanted to toil away all day for no reason; they exist to create things for others to enjoy. So, how well or easily shoppers can enjoy those

things isn’t a tiny technicality to toss aside. When observers step back and look beyond the simple fact that John Doe lost his Playa Bowls job to a robot, the painting suddenly becomes brighter. An electric mermaid bowl suddenly doesn’t cost as much to make, so profits increase.

Better yet, because Playa Bowls needs to compete with other restaurants, prices have more room to fall. More money is suddenly in the hands of beachgoers and the Playa Bowls owners to spend or invest in other companies, where profits and even employment grow. The cycle spirals onward and outward.

When 2040 rolls along, students may or may not be able to live out the tradition of getting working papers from Mr. Gleason and working the summer away. Beyond that, unemployment among specific demographics may still rise at the hands of these new machines.

Yet, in the basic scenario described above, people and society as a whole are better off. Future Americans will collectively become better off as we find the new jobs of tomorrow that we can’t fathom today. We will buy the things that are getting better and cheaper because of the same allegedly negative threat that put us out of work in the first place: automation, the age-old scare that has doubled as a blessing in disguise.